DRUID CLOCK

Derevo Theatre | Sharmanka | 2005

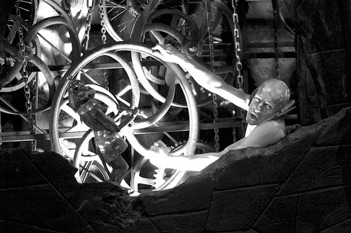

In 2005, Eduard Bersudsky won a Creative Scotland Award, which gave Sharmanka a unique opportunity to collaborate with the renowned Derevo Theatre. The kinemat Tree of Life, based on both Slavic and Celtic beliefs in the magical relationship between humans, trees and animals, became part of the performance The Druid Clock at the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh at New Year 2006. The performance took place in the Museum’s entrance hall and incorporated the giant Millennium Clock Tower, made by Eduard with Tim Stead, Annica Sandström and Jürgen Tübbecke (1997-99) for the Museum.

Director | Anton Adasinsky

Lighting | Sergey Jakovsky

Sound | Daniel Williams

NOW THEIR TIME HAS COME

The HERALD, December 30 2005

MARY BRENNAN

Important details first (and reasons later). This afternoon, at 2.30pm in the main hall of the Royal Museum in Chambers Street, Edinburgh, Derevo will perform the final part of The Druid Clock – a free event that, in the face of our frantic scavenging for end-of-year sales bargains, cuts deep into the spiritual heartland and elemental nature of the turning year. Go, and you’ll take away images and ideas that will far outlast any cut-price fad.

The Druid Clock is an idiosyncratic dream-work made possible by one of the Scottish Arts Council’s 2005 Creative Scotland awards. Eduard Bersudsky, the driving force behind the kinetic sculptures known, collectively, as Sharmanka, had long cherished the possibility of collaborating with Derevo, whom he affectionately hails as fellow “exiles” from St Petersburg.

Bersudsky had first come in contact with Anton Adasinskiy and his dance-theatre group some 15 years ago and had immediately sensed an artistic kinship between his own fantastically grotesque, symbolic sculptures and Derevo’s intensely physical, profoundly allegorical performances.

Already, in his mind’s eye, he could see how the movement and meaning within his sculptures connected with Adasinskiy’s judderingly expressive choreography and its recurring themes of conflict between good and evil, damnation and redemption. He hankered after a dialogue between the articulated metal of his artifacts and the responsive bodies of Derevo’s dancers but, as he says himself, “there was never a producer crazy enough to invest money into such a risky business”.

Years passed. Bersudsky and Sharmanka put down roots in a Glasgow studio, Derevo – from their relocated base in Germany – became an internationally acclaimed touring company. Each time the award-winning company appeared on the Edinburgh Fringe, Bersudsky’s thoughts would hark back to the “what if . . . ” notion of collaboration.

Living and working in Scotland had added new frames of reference to his personal commentary on society past, present and future. Derevo, too, had been exploring other cultures in their work and – like Bersudsky – finding potent common ground across countries and centuries. For even as we increasingly rely on electronic technology to tell us where we are, and even who we are, there still exists an ancient calendar of myths and rituals – the bringing of evergreens into the house at Christmas being one – that influences our behaviour.

The Druid Clock taps into that realm of mystical forces. With Bersudsky’s massive Millennium Clock as a backdrop, Derevo unleash the spirits of his sculptures in a dance-work full of wonderful mischief and poignant humanity.

They arrive among us in a gust of jazzy circus-fanfares (composed by Daniel Williams). All six are uniformly shaven-headed and (initially) clad in brisk black – only the splodges of white on skin and suits alike suggest they may have risen from some region under-the-ground.

Capering and leaping, clambering up the pillars in the museum’s stately hall, they embody all the subversive energies of Saturnalia, misrule and yuletide revelry.

Once inside the cordon that creates an impromptu performance space, they discover a rope maze and as they trot along its lines, they tease us into a mythic landscape peopled by demons and sprites. The black clothes are cast aside, and near-naked forms in pale tatters emerge to re-enact aspects of long-ago cults – with the “green man” a major player in a pageant that makes a dark, magic poetry out of old Slav and Druid beliefs about life, death and the forest, where souls of the dead were held to enter trees and so be reborn.

When Adasinskiy and his dancers curl and contort their frames, they look like Bersudsky’s carved grotesques and echo his symbolic intentions with an understanding rooted in that shared experience of St Petersburg days.

Change and decay are accepted, because with skill and imagination something new can be created – like the recycled scrap so resourcefully deployed in Bersudsky’s sculptures. And when, as in The Druid Clock, those sculptures combine with Derevo’s wise mayhem the result is a memorable way of seeing the old year on its way.