WOODEN KINEMATS

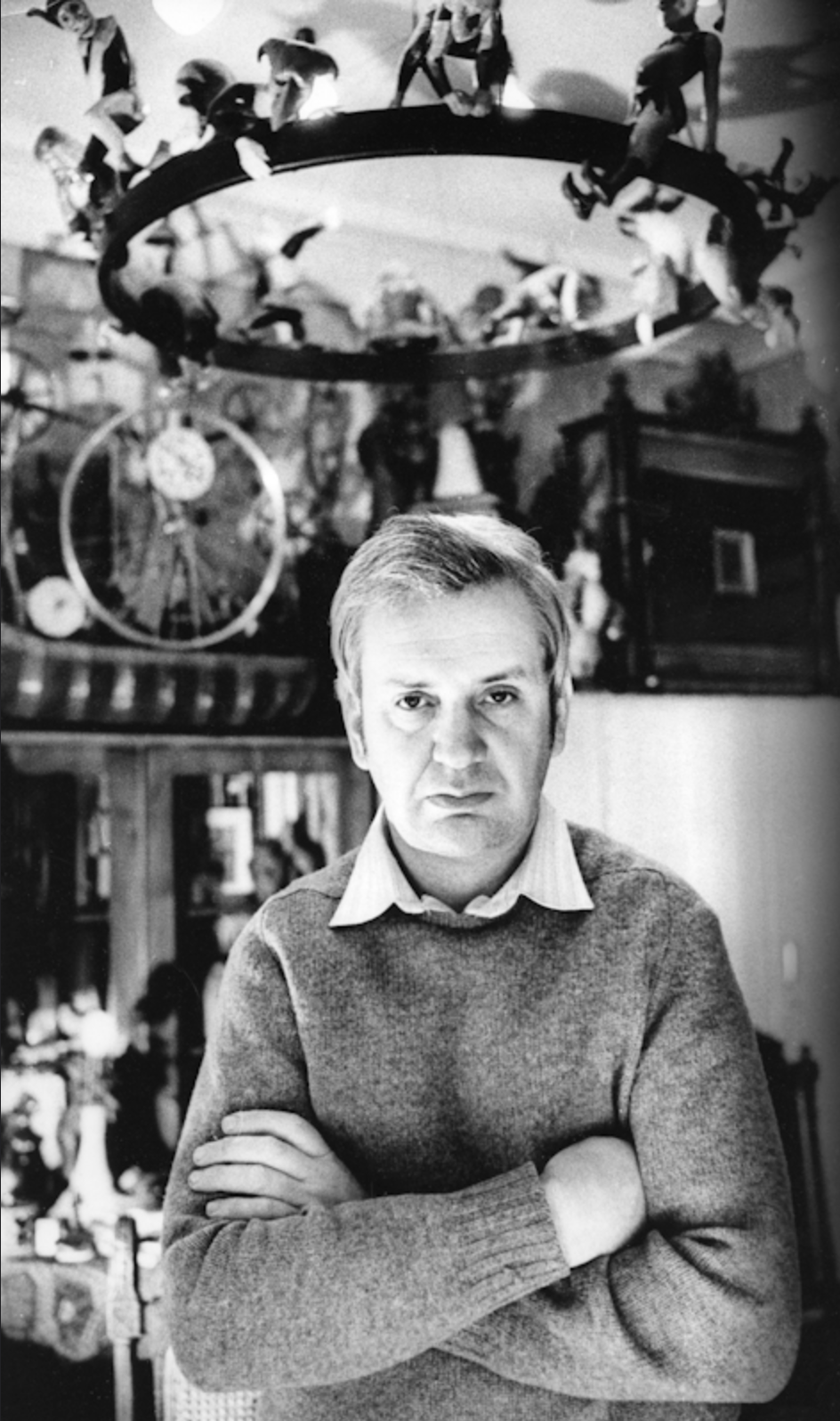

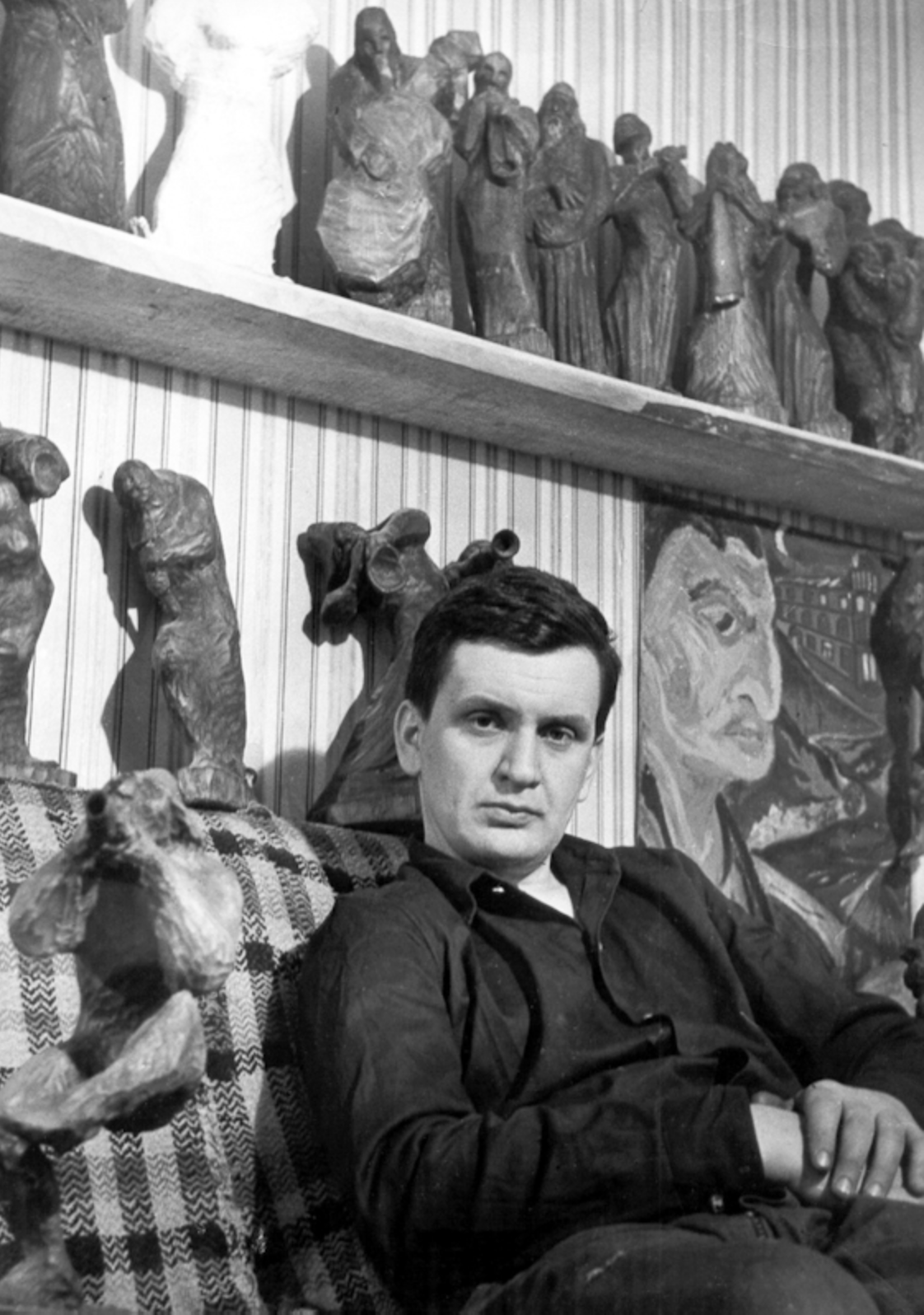

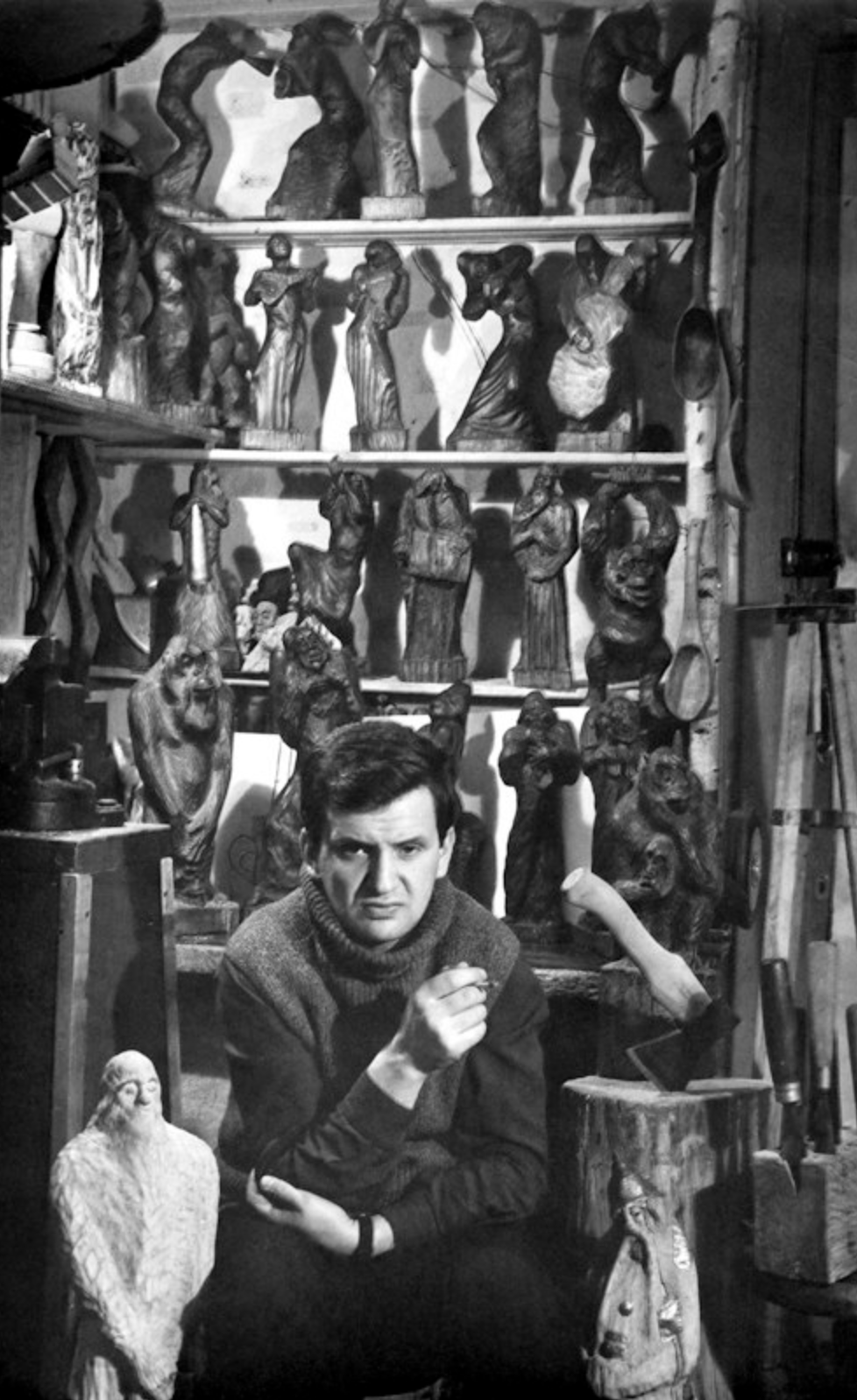

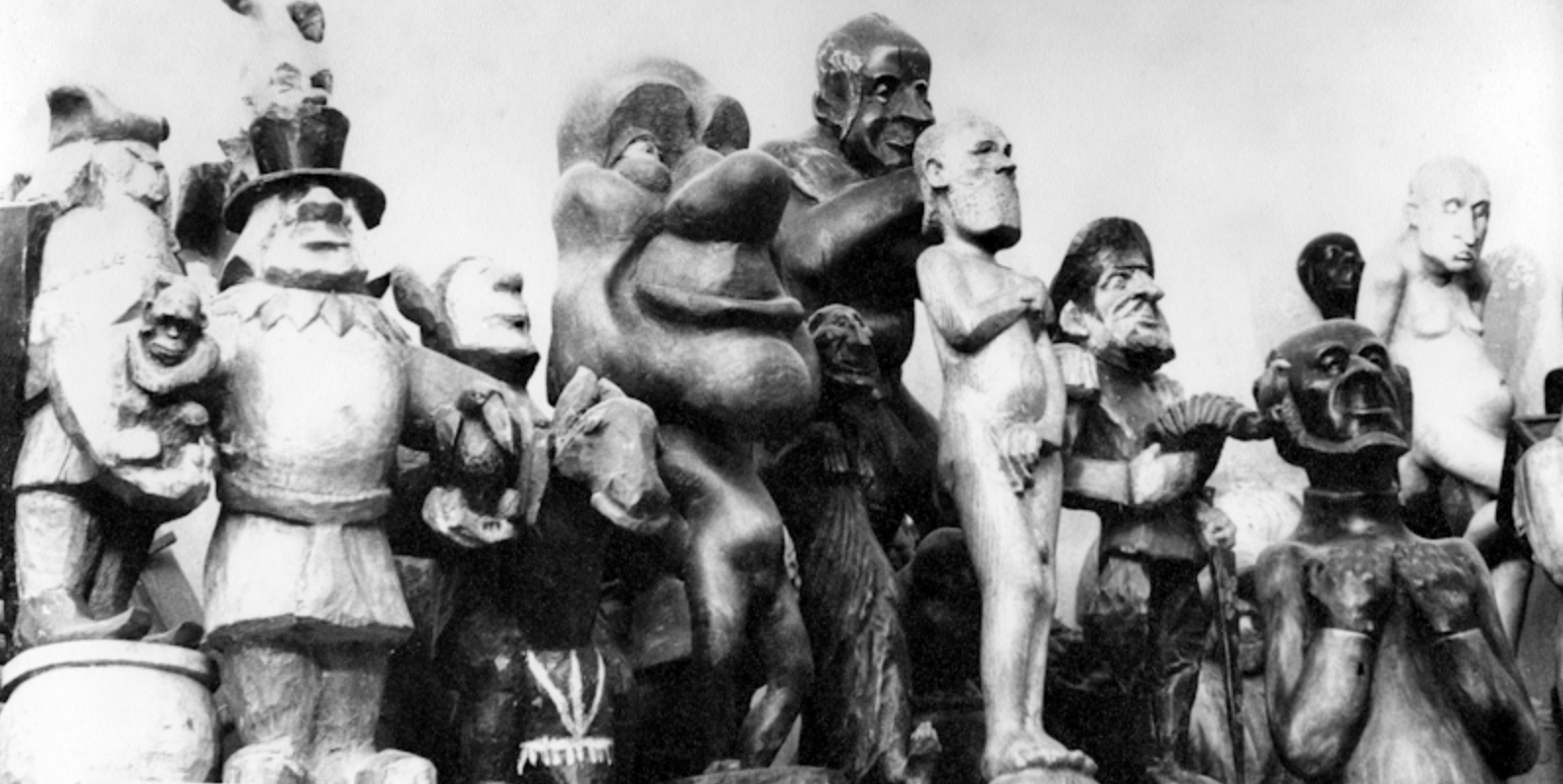

The original collection made in St.Petersburg prior to Sharmanka’s opening to public.

This set of Kinetic Sculptures was made by Eduard Bersudsky in his only living space, an 18 square metre room in a communal flat in Leningrad in the 1970s and 80s. He could not even dream of exhibiting them. From the Soviet authorities’ point of view, they were ideologically and aesthetically incorrect. The materials for this universe were the remnants of carved furniture, the wheels of Singer sewing machines and old motors, stolen from factories by friends or got on the black market in exchange for a bottle of vodka. He carved figures, painted them and then dried them on the huge gas-boiler, which he operated to make his living.

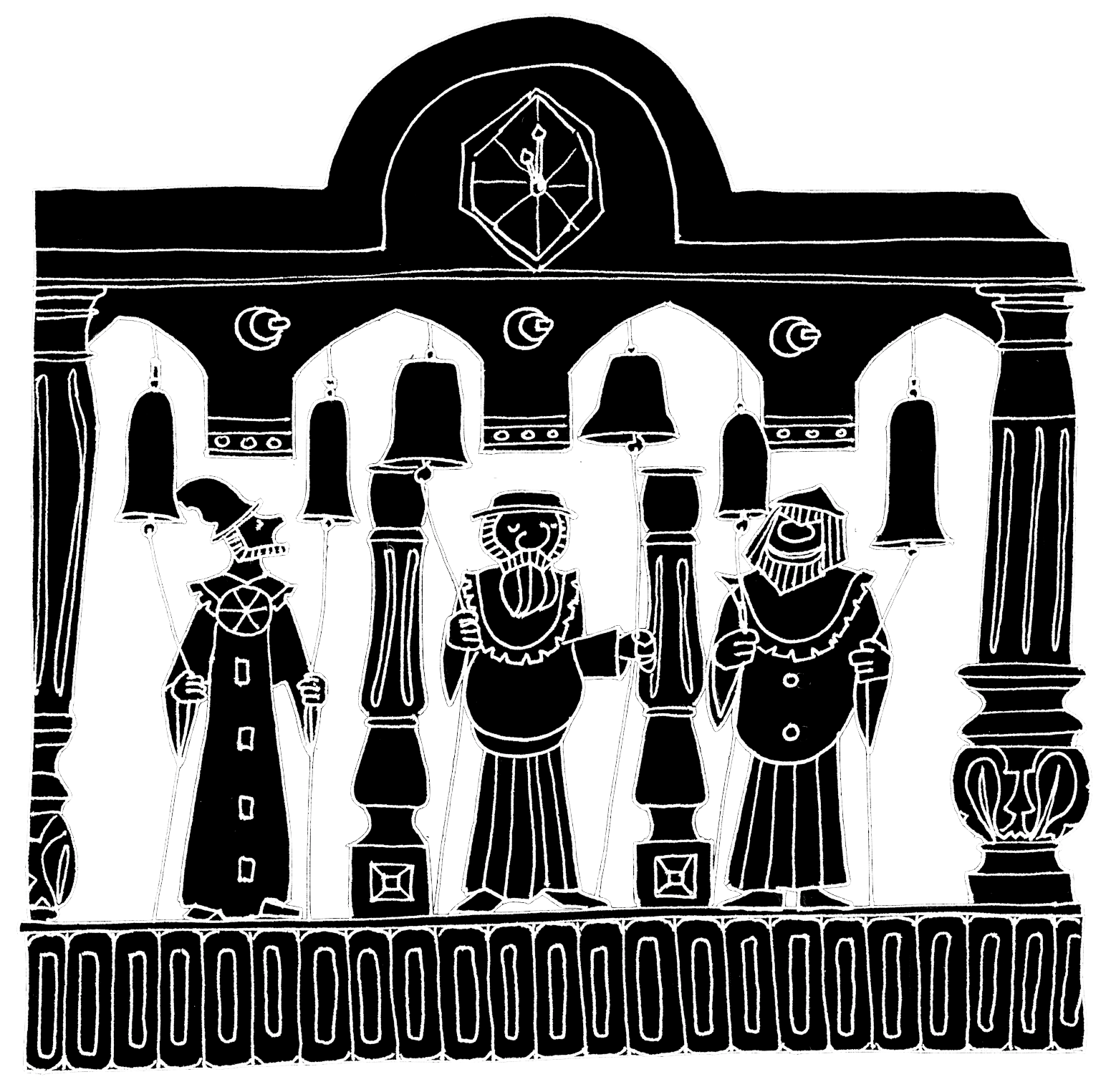

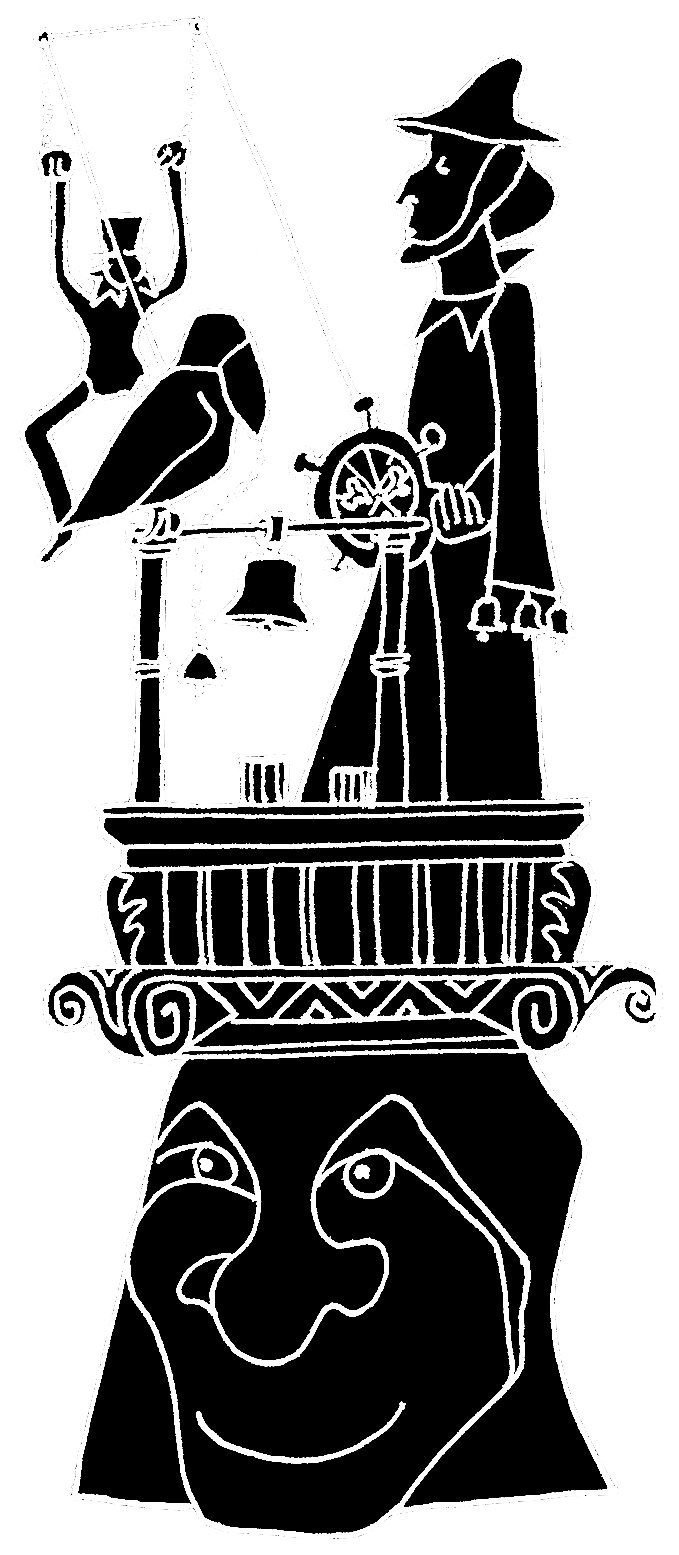

THE BELL RINGERS (1969)

Bell ringing in old Russia was a hard, skilful and demanding job. There was no mechanical device, a bell-ringer had to climb to the top of a tower, open to all winds and pull heavy ropes by hand. In the country with no mountains and vast plains, he was the only one who could see for miles around. He would warn of disaster, of the approach of the enemy and he would also celebrate feast days.

The bells were the voice from the earth shouting to heaven and the bell-ringer‚ job was a sort of spiritual sentry. We grew up in a dumb country‚ bells were forbidden under the Communist regime. Most of them had been thrown down from the belfry and sent to the foundry. The few that were left were only allowed to be rung on rare occasions, such as important church festivals, and then only muffled. Maybe this is why there are so many bells in Eduard’s kinemats.

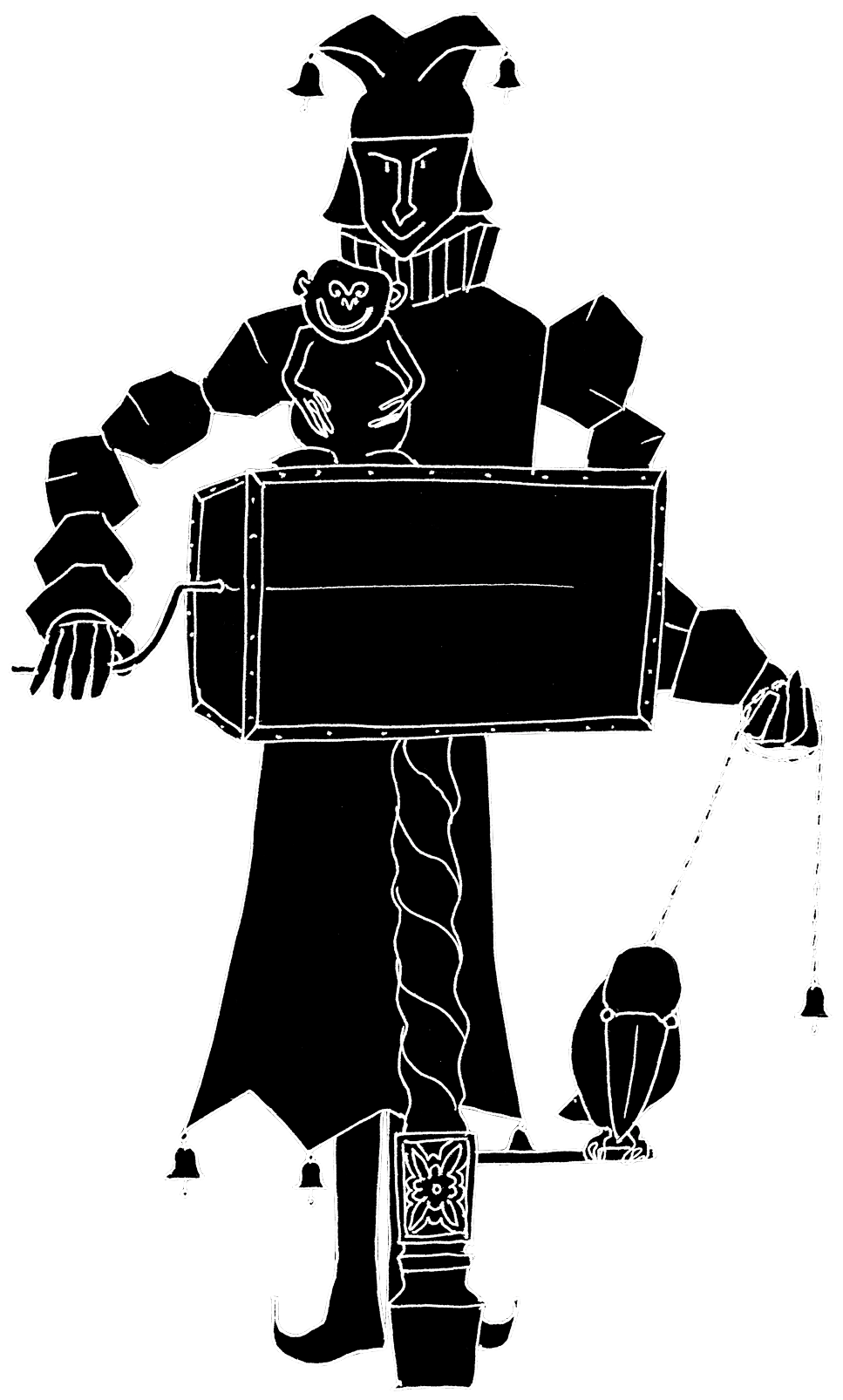

SMALL ORGAN GRINDER (1975)

& BIG ORGAN GRINDER (1981)

Sharmanka is Russian for barrel organ or hurdy-gurdy. This early mechanical music device came to Russia from Europe 200 years ago and the first tune of their repertoire was Charmante Catherine, from which Russians made the name sharmanka and Polish‚ katrinka.

In Western Europe these instruments are associated with fairs, having a good time and a certain amount of nostalgia or escape from the weight and greyness of city life, as in the painting The Organ Grinder by L.S. Lowry. In Russia they are associated with the repeating cycle of life, the sun rising after the night, hope returning after despair. They symbolise patience, hope and the inevitability of fate calling the tune.

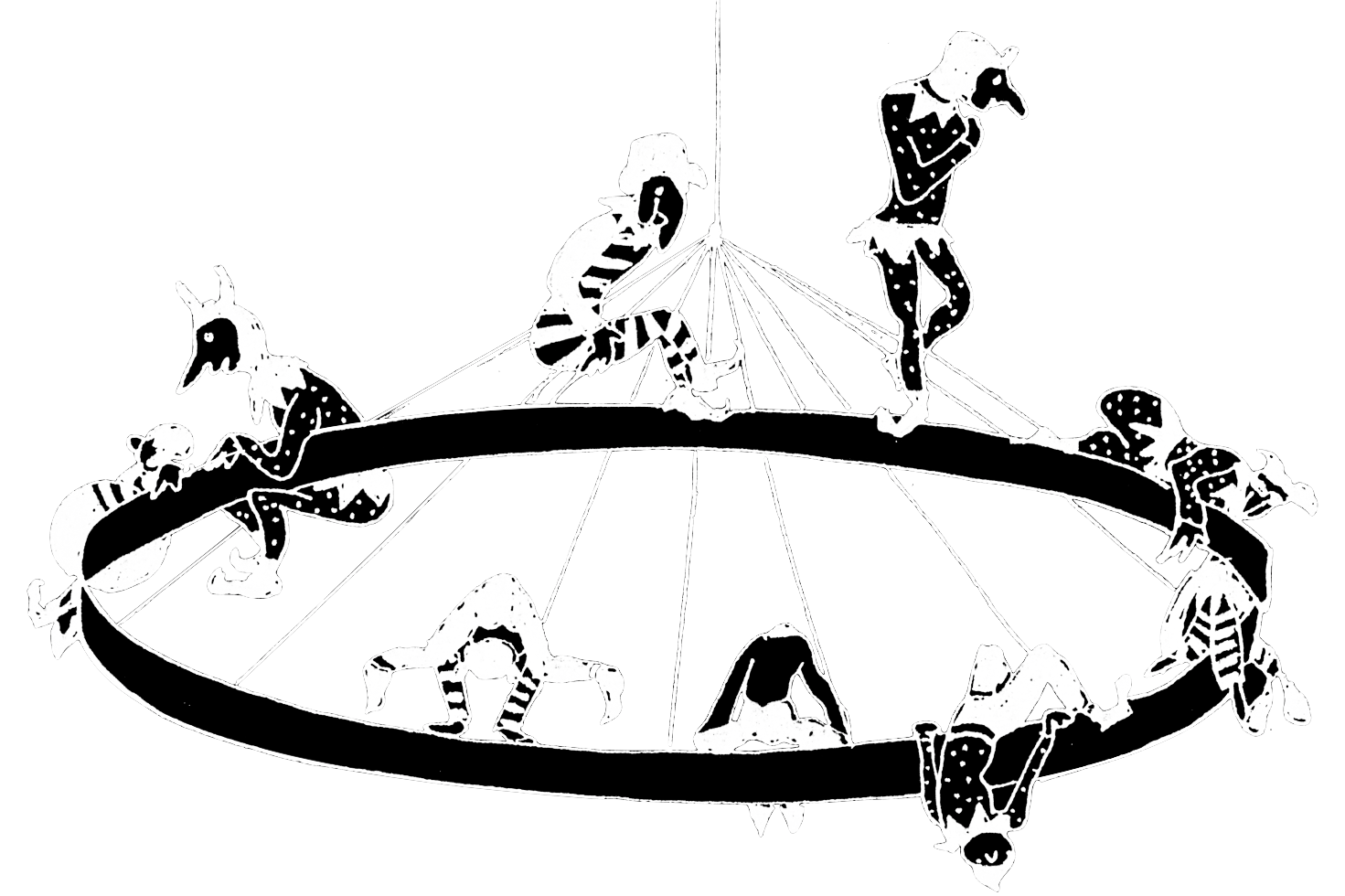

CIRCLE OF CLOWNS (1978)

THE HEAD (1979)

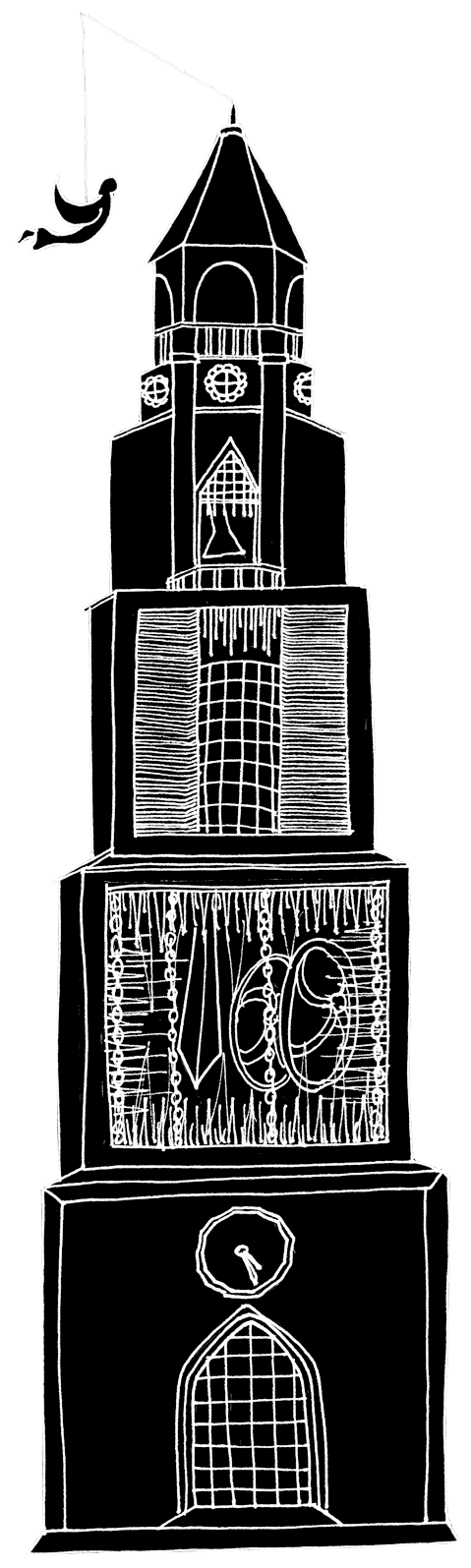

CLOCK OF LIFE (1980)

The curtain opens to reveal figures of the circle of life, from birth to death.

HUNCHBACK (1982)

“As a child I lived on the corner of Dostoevsky and Candle Streets. There were often beggars in the doorways. They had accordions and as soon as they started playing, everybody would open their windows to watch them, then wrap money up in bits of paper, as much as they could, and throw it down. The children who were with the beggars would look for it. Everyone would point and shout: “There is some, over there.”

It was the time of the postwar collapse. We had to survive. For some reason I remember a man in a hat. He had a box and on it was a guinea pig and in front of the guinea pig was another small box. The man would take money from passers-by and tell the guinea pig:

“Come on, Mashka, look for it.” The guinea pig would bend its head and from the box take a piece of paper, on which was written the fate that awaited the person.”

– Eduard Bersudsky

THE CASTLE, OR 1937 (1983)

1937 was the most cruel year of Stalin’s “purges” but not the only one. Millions were executed and sent into labour camps, among them famous poet Osip Mandelshtam. One of the four severed heads inside this killing machine is his portrait, others are a famous writer, an actor and a woman-poet, all of whom became victims of the regime ‚- just four out of millions of men and women whose names we do not know.

“Sometimes I have this nightmare: I’m in a camp, in some sort of ghetto, in a small room, and tomorrow I am going to be tortured and then chased to some enormous ditch where I’ll be shot at with machine guns. I made The Castle when thoughts were going round and round in my head about twenty million people dying for nothing. I felt sorry for these people why do I live and they do not? Why, for example, is Mandelshtam lying under the ground? He would have been able to tell this world a lot more but for some reason they took him like a mere cockroach and squashed him. And who did this? People who are not even worth his little finger. I remembered Kafka – his machine with needles. A person was put into this machine and it would lay out on his back some sort of writing, then it would write on his chest. He jerked around from the needles but the machine continued to write on him”.

Eduard Bersudsky

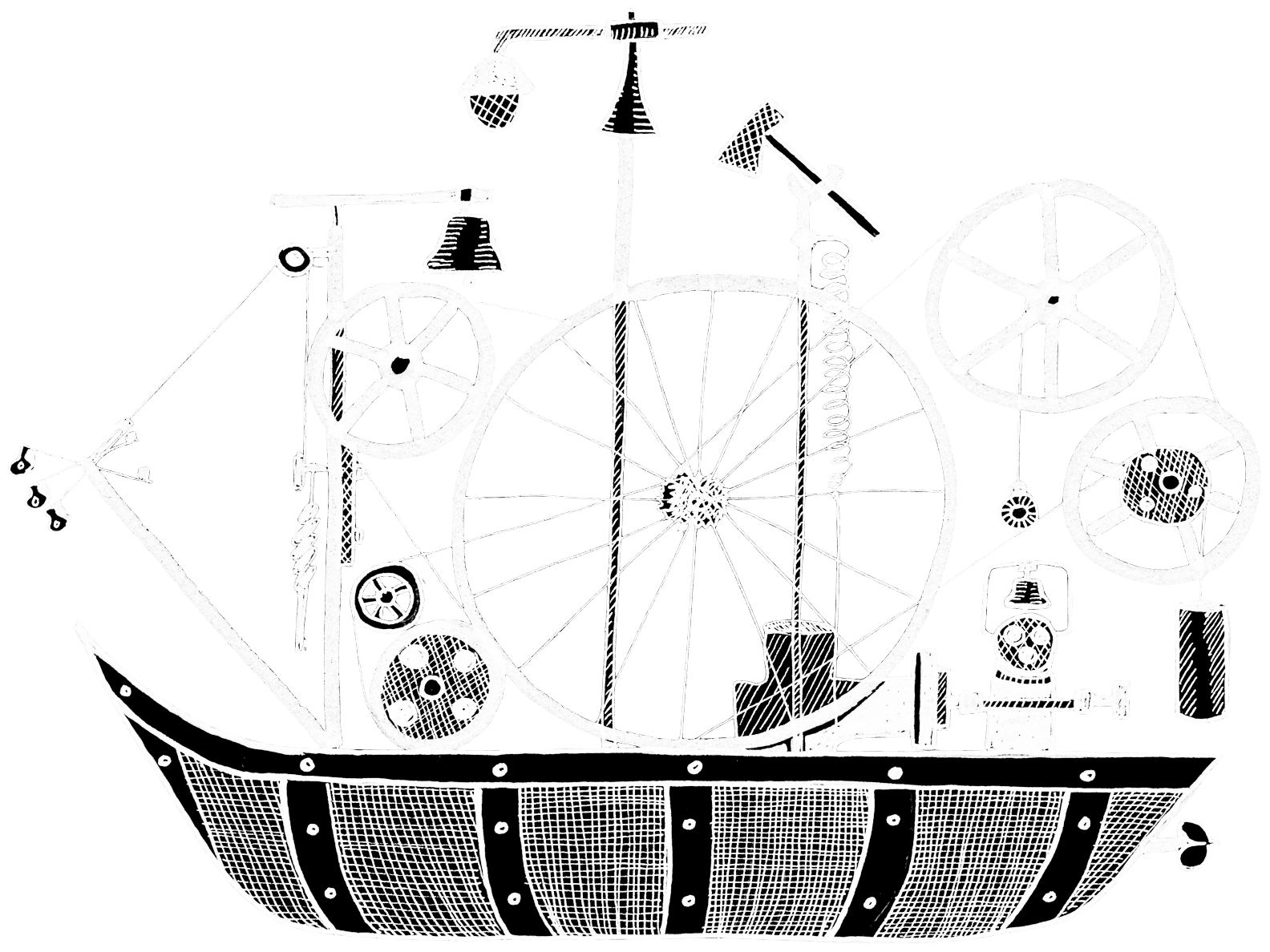

THE SHIP (1985)

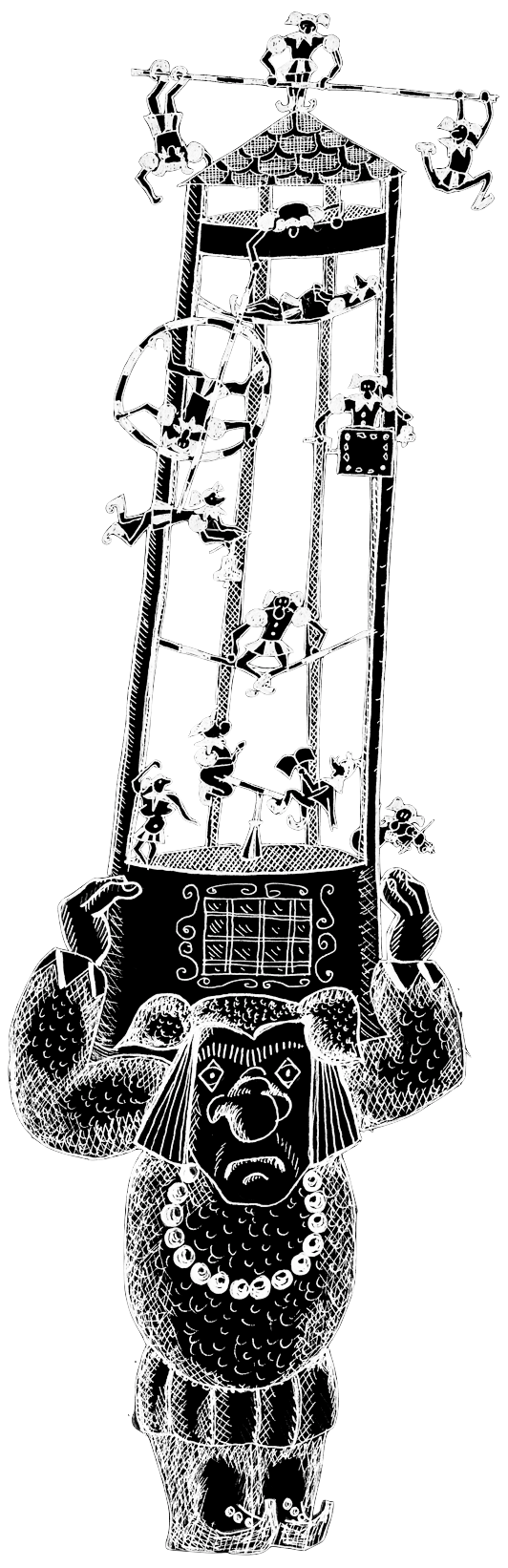

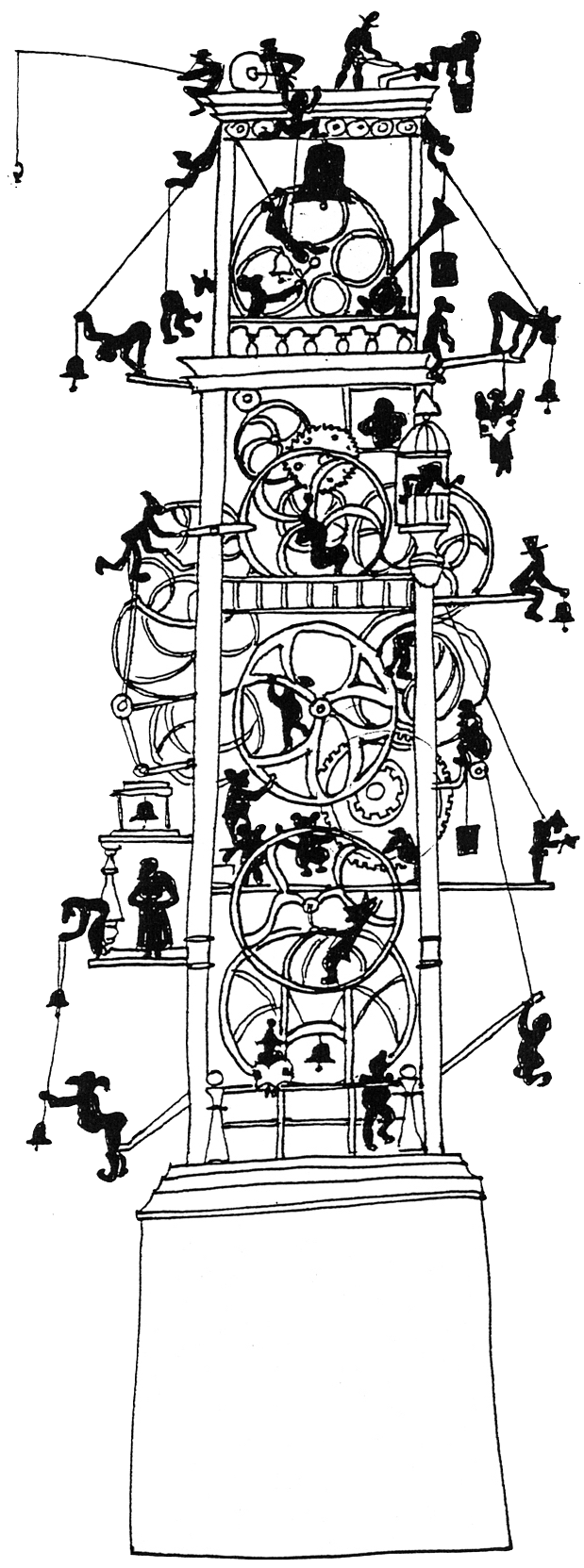

TOWER OF BABEL (1986-88)

There is a story in the Bible that tells of the attempt by Babylonians to build a great tower, which would reach into heaven so they would be “like gods”. They could never finish or agree on it being finished. The Tower of Babel became a symbol of a futile attempt to build something ultimately grand. Everybody at this tower is frantically busy and yet nothing really happens. Everyone has an illusion of the importance of his work, of his power. But follow the pulleys, wheels and strings: they lead you to somebody else who thinks that it is him who is in control.

There are some characters from Russian history depicted: Lenin making his speech and Stalin with his axe.

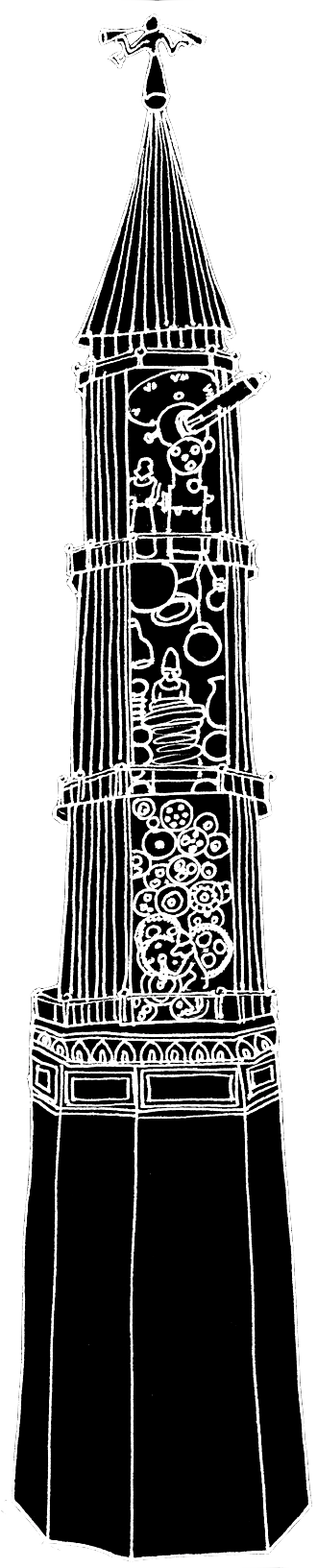

TOWER OF MEDIEVAL SCIENCE (1989)

This kinemat has four levels: at the bottom is the mechanic keeping the cogs turning; the next level is the alchemist brewing up magic; above the astronomer searches the stars for their secrets; on the very top the Archangel blows a trumpet to the four corners of the earth.

“One of my first childhood memories is of our communal kitchen, full of smoke from the oil stove where someone was cooking, a neighbor rubbing kerosene into her daughter’s hair to kill lice, others engaged in all sorts of chores. I found a box with ventilation holes, stuck noses onto walnut shells, pushed my fingers through the holes and put the shells on my fingers. By moving them I could create the illusion of people having a lively conversation. I must have been about eight years old. Now more than 60 years have passed and I am still playing with my theatre”. -Eduard Bersudsky